Gently pushing aside the potato plant, her fingers delve lightly into dark soil. She finds a small potato, and smiling, holds it up for us to see.

Shaelene Grace Moler grew up in Ḵéex̱’ Ḵwaan, the small community of Kake in Lingit Aani (Southeast Alaska), located approximately 50 minutes southwest of Juneau by seaplane. Seaplanes and boats are the primary modes of transportation here, hence the time measurement to show distance.

Her Tlingit name is Sgweín and she is of the Tsaagweidí, the split-finned killer whale clan, from the yak’s lits’eix̱i hít, the house that once anchored the village.

Having grown up in Kake, twenty-five-year-old Shaelene works for Spruce Root as the Sustainable Southeast Partnership (SSP) Communications Catalyst. SSP and Spruce Root, partners of Home Planet Fund, work to strengthen cultural, ecological and economic resilience across Southeast Alaska, an area covered by the Tongass Rainforest.

The Tongass is one of the most ecologically important places on Earth, and plays a critical role in the global environmental crisis by sequestering one billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. The towering old growth forests of the Tongass store the carbon equivalent of six million cars a year, while producing a quarter of all the salmon in the Pacific Northwest.

This intact and abundant rainforest are the homelands of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian Peoples, who care for, steward, and honor the lands and waters that sustain all Southeast Alaskans. Communities in this region practice a way-of-life that is rapidly disappearing across the globe.

SSP envisions self-determined and connected communities where Southeast Indigenous values continue to inspire society, shape relationships, and ensure that each generation thrives on healthy lands and waters.

“The folks working on this bring up seaweed for fertilizer to lay atop the potatoes,” Shaelene explained, then pointed over the water of the nearby bay, to a nearby shore. “There is another garden nearby as well, just around the curve in the shoreline there.”

Photo Credit: Julie Ellison

We are at a bay not far from the village of Kake.

Shaelene was excited to show us the Tlinglit potato, which has never touched European soil. The potato garden she is showing me and photographer Julie Ellison is a project the Alaska Youth Stewards (AYS) assist with, as well as learn from.

The AYS, a project within the SSP, delivers programs in rural communities of Southeast Alaska and is a partnership including Tribal governments, Tribal corporations, conservation groups, federal and state agencies, not-for-profits, community entities, and committed individuals. Youth (ages 14-25) are recruited from throughout the region to gain experience in fisheries, forestry, engineering, recreation, community service and cultural stewardship. Core partners include the US Forest Service, Sealaska Corporation, National Forest Foundation, Organized Village of Kake, Hoonah Indian Association, Chatham School District and Craig Tribal Association.

AYS employs a new generation of cultural and community leaders to care for their lands, waters and communities through on-the-ground restoration and community stewardship projects like this potato garden. This program provides youth from rural Southeast Alaska well-supported pathways to becoming leaders who contribute to the region’s culture, economy, food sovereignty and security, and ecological resilience. Perhaps most importantly, their work is rooted in Indigenous Knowledge thousands of years old, and driven by community priorities and needs.

The potato garden project is led by locals Miakah Nix and Carson Viles, and is something AYS helps maintain during the summer months.

Shaelene told us that potatoes from these gardens are harvested for eating, of course, but are also planted in elders’ gardens at their homes in the village.

“It has always been our tradition to plant these gardens along beaches, and now we are doing it once again.”Shaelene Moler

AYS projects meld community needs, food sovereignty, food security, and tradition into an action that sustains everyone participating.

Now in their eighth year, other AYS projects include traditional food harvests and community garden development, trail construction and maintenance, stream restoration and ocean monitoring.

Shaelene took us along the shore to the other potato garden. The side closest to the water was held in place by a rock wall, the upper portion of the garden hemmed in by forest.

This is far from the only project of its kind Home Planet Fund partners are working on in this area. Other projects include food sovereignty and security, healing practices, mariculture, youth stewardship, salmon stream rehabilitation in the wake of clear cuts, and many others.

Back in Kake, in the shallow waters of the shoreline west of the village, a pilot project for a clam garden is underway. It is part of an effort to revitalize the traditional practice, and is the first contemporary clam garden in Alaska. Following tradition, it is also deliberately located nearby the village for ease of access.

Working with the tribal natural resources department, 20-year-old Ethan Kadake is now the Shellfish Garden Coordinator for his tribe. His work within AYS prepared him for this position, which he has been in for the past year.

Standing on the shore overlooking the area of the garden, which was underwater due to it being high tide, Ethan discussed some of his work.

“I work to keep sea otters and starfish, the natural predators of clams, from eating our harvest,” he explained. “We also aim to construct several more locations for these gardens. This one has been here since 2020.”

While the clam gardens have not been harvested yet, they are already located on a productive clam bed. For now, they serve primarily as an education project for community members as well as other communities, serving the traditional function of enhancing and expanding clam habitat that will be harvested in months where harvest is limited.

When it is harvested, like the Tlingit potatoes, they will be shared with elders and others throughout the village.

“It is good being in touch with the land and water, and harvesting,” he offered. “This gets me helping the community. We harvest every few weeks during the negative tides. The cockles are a delicacy, and we usually harvest butter clams.”

The tribe has always known that these clam gardens support the local ecosystems where they are located, as well as prevent coastal erosion. Baby crabs, octopus and other sea life are naturally attracted to and supported by these clam gardens.

Further out in the water from the clam gardens is Grave Island, where Kake’s cemetery is located.

The graves of the ancestors are maintained by AYS, along with the trails there people use to access the area.

Kaax̲waan Dawn Jackson, the Executive Director of the Organized Village of Kake, joined Ethan as we stood on the rocky shoreline above the clam gardens.

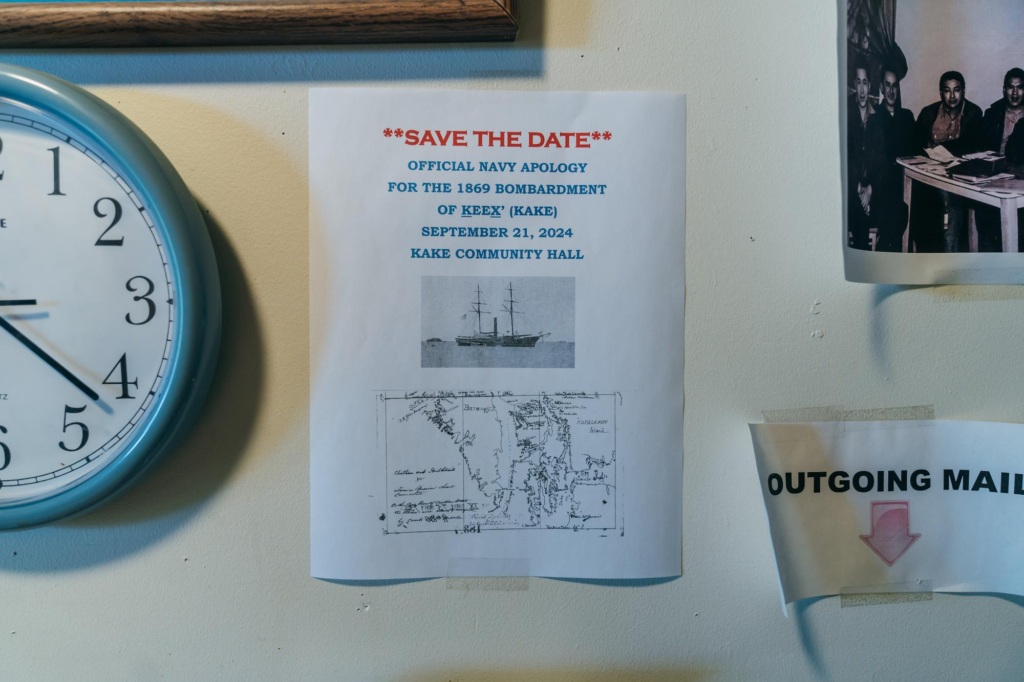

She informed us of how, in 1869, the U.S. Navy bombarded the village of Kake. On September 21, 2024, the Navy sent representatives to Kake and issued a formal apology. After more than a century and a half, healing is indeed taking place.

Dawn, who is also on SSP’s steering committee, attended the University of Washington where she studied archeology. After graduating, she prioritized coming back home to work for her people.

Her pride for Ethan, the clam garden, and the work of AYS and SSP were evident.

“We’re working with the Swinomish people of Washington State, sharing information with them and the First Nations people of Victoria, Canada,” she said.

Later that evening, while we drove along a dirt road back to Kake from the potato gardens through a thick evergreen forest, Shaelene slowed as a large moose strode across the road in front of us.

A little further, a large black bear ambled alongside the road, turned, and disappeared into the forest.

As we continued along the bumpy road, Shaelene explained how Kake has “all the berries of the region. Thimble berries, wild strawberries, cloudberries, blueberries, elderberries, various cranberries, and salmon berries.”

There are deer, black bear, and moose, although moose are uncommon for islands across the region.

Shaelene’s younger sister, 22 years old, just completed an internship with Spruce Root, and was looking forward to continued work with them.

For Shaelene, she takes every opportunity she can to come back to her home village, and has no desire to leave the region. Like so many others in Kake, she was excited for the upcoming moose hunting season.

Her story, and that of her family, is but one example of the importance of these projects.

In Kake alone, there are between four and eight kids working with AYS. Between the Organized Village of Kake, SSP, U.S. Forest Service partnerships with the tribe, and interns, there are now 20 to 30 jobs being provided on any given time period.

One of SSP’s core values centers on justice and healing.

“Our work aims to disrupt the systems of oppression and colonization that continue to harm our communities today,” states their website. “We support the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian processes of reclaiming power and healing from trauma. Our Partnership holds deep reverence for Indigenous values as we build a more just and equitable Southeast, today and for the next seven generations.”

Our work aims to disrupt the systems of oppression and colonization that continue to harm our communities todaySustainable Southeast Partnership

They, like those they work with, including Home Planet Fund, believe that the sincerity of our process is as important as the outcomes of our collaboration. This is why all of this work is built upon a foundation of trust; a trust that is established and maintained over time through respect and reciprocity.

These projects and many others like them are quite literally weaving traditional knowledge, culture, and Native values more deeply into these villages and communities across Southeast Alaska.

They center Indigenous values, starting with this: “Kuxhadahaan Adaayoo.analgein.” (Stop, observe, examine, act).

And this is exactly what is happening across Lingit Aani (Southeast Alaska).