Her relatives were bombarded by the United States. Navy in their village of Angoon, Alaska on October 26, 1882.

She also has blood relatives in Kake, another village that was bombed by the Navy in January 1869.

“It’s heavy, but it’s what I’ve been experiencing and living since I was a child and started speaking up about it,” Jamiann Hasselquist, the Regional Healing Catalyst for Home Planet Fund Partner Sustainable Southeast Partnership (SSP) in Southeastern Alaska said of her life.

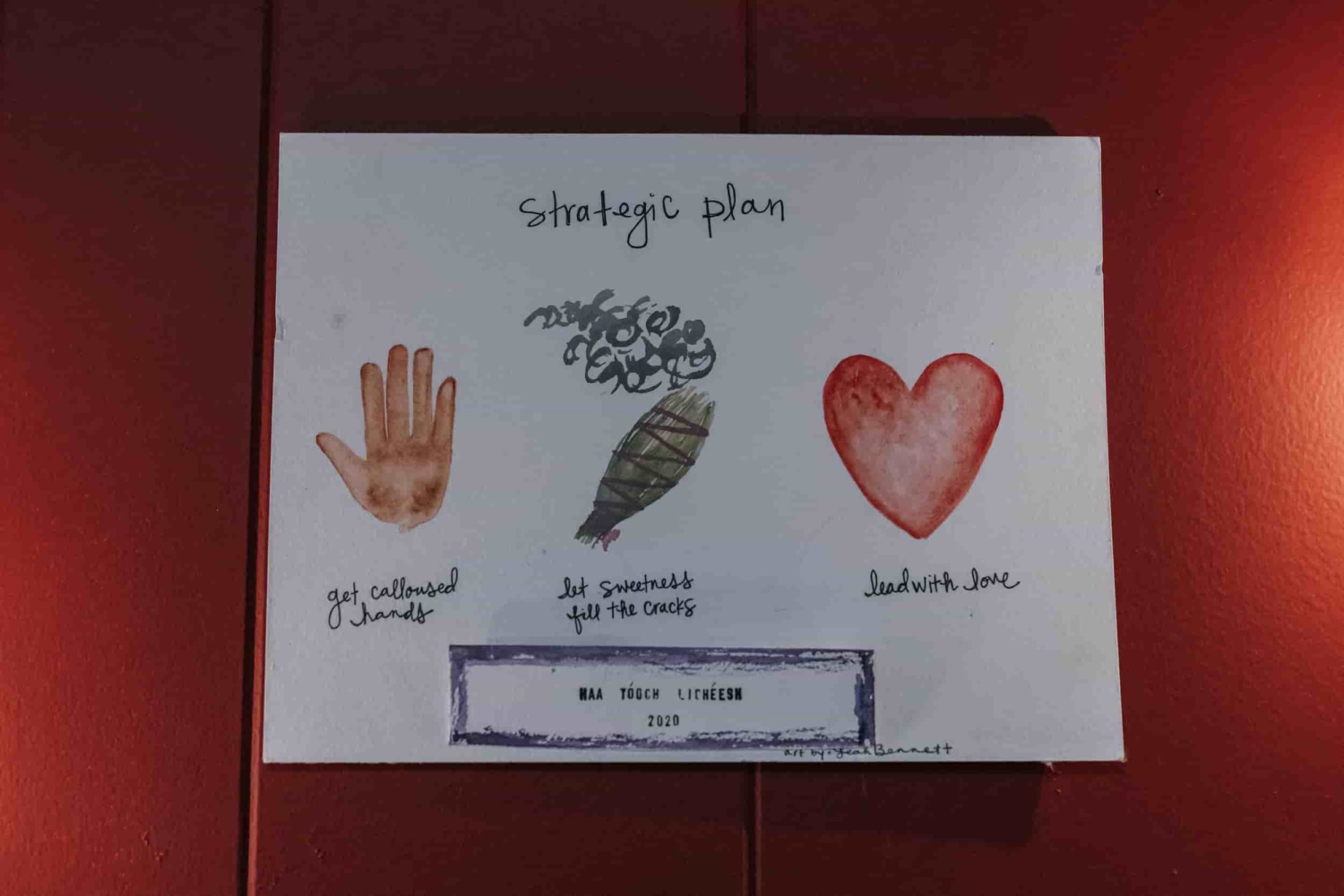

Jamiann is the Healing Catalyst for Haa Tóoch Lichéesh (HTL), which is Lingít for “We Believe it is Possible.” HTL is a non-profit that partners with more than 20 organizations to host healing events, youth programs, and equity trainings.

She moved and talked with a quiet earnestness.

“I remember my first protest was with my aunt and mother when I was five years old, and that was against them for cutting my hair.”

“We brought eagle and raven feathers there, sung, and we all cried heavy tears. We talked about how the songs and drum beats permeated that building and brought healing to what happened there. We followed the lead of the people of Sitka putting raven and eagle feathers that were left standing in the ground, to represent both the Raven and Eagle clans, to bring balance as is our tradition.”Jamiann Hasselquist, the Regional Healing Catalyst for Home Planet Fund Partner Sustainable Southeast Partnership in Southeastern Alaska

It was her own healing journey that led her into her current work.

“Two different organizations saw me doing ocean dips, MMIP [Missing and Murdered Indigenous People] work, cemetery clean-ups, and Orange Shirt Day.

Orange Shirt Day is meant to honor survivors of both day and residential boarding school institutions and the generations following them, recognize the damage caused by the colonial system, and promote reconciliation.

In this way, Jamiann quite literally lived her way into the job.

“They created this job and invited me to apply” she said.

The HTL office where we met is an oasis of calm amidst a downtown that was swarmed with tourists from massive cruise ships anchored nearby.

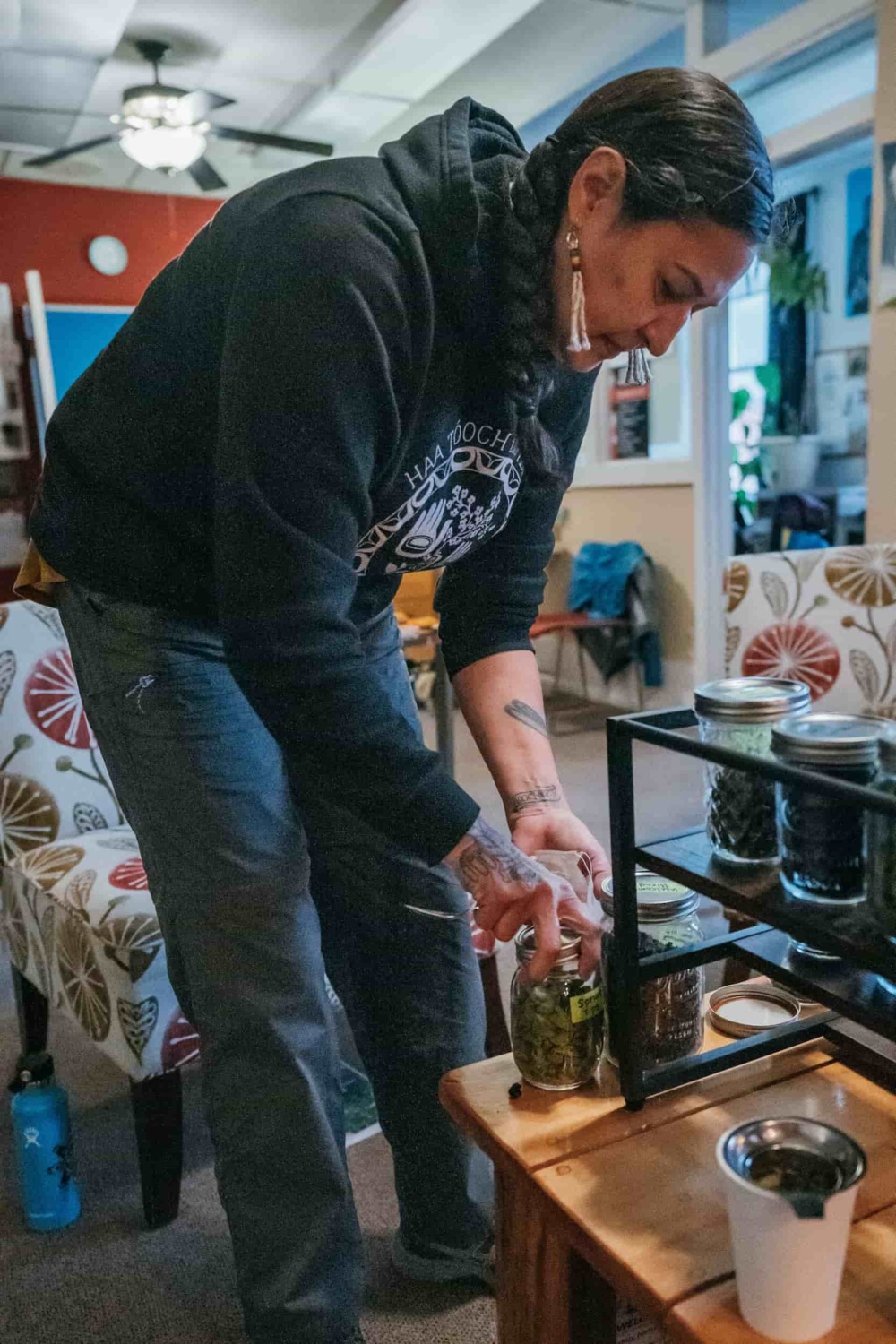

Welcoming people with a ceremonial tea bar, Jamiann asked photographer Julie Ellison and myself to choose what we “felt called towards” to add to our tea from the bar, which included jars of spruce tips, rosehips, fireweed, and peppermint, among other herbs.

After making sure her guests were situated with the teas of our choosing, Jamiann made herself a mug, sat down, grew quiet for a moment, then softly thanked her tea before taking a drink.

She joined SSP as their Healing Catalyst in the fall of 2023 but had already been involved with HTL for two years by then.

President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood, the oldest known anti-discrimination organization in the world, Jamiann now works across Southeast Alaska to promote the healing of individuals and institutions, including work in cultural revitalization, restorative justice, and much, much more.

“On a rainy day I went outside and just stood in the rain. I listened to the rain, and I heard my grandma and our people. I had a vision of what was supposed to happen…I felt my people behind me. I was standing in the village where the old Alaska Native Brotherhood hall used to be, so I was seeing, hearing and feeling spirit from there.”Hasselquist, the Regional Healing Catalyst for Home Planet Fund Partner Sustainable Southeast Partnership in Southeastern Alaska

Jamiann told story after story of trauma and healing as she showed us around her small office. In a separate room, she keeps a large white board that has all her ongoing projects, each of which a direct healing of some kind for her people.

One of the stories she shared was of a school building on nearby Douglas Island, which happened to be the last standing segregated school in the state back in its day.

For healing purposes, Jamiann called several people together to meet there for a ceremony.

“We brought eagle and raven feathers there, sung, and we all cried heavy tears,” she explained. “We talked about how the songs and drum beats permeated that building and brought healing to what happened there. We followed the lead of the people of Sitka putting raven and eagle feathers that were left standing in the ground, to represent both the Raven and Eagle clans, to bring balance as is our tradition.”

This led to more healing drum group ceremonies, which then led to her partnering with other groups for cleansing ocean dips, graveyard clean-ups to honor their ancestors, and increasing awareness across the region for the need for deeper healing for her people.

“On a rainy day I went outside and just stood in the rain,” Jamiann explained. “I listened to the rain, and I heard my grandma and our people. I had a vision of what was supposed to happen…I felt my people behind me. I was standing in the village where the old Alaska Native Brotherhood hall used to be, so I was seeing, hearing and feeling spirit from there.”

After seeing many other things, Jamiann knew the vision told her what needed to happen. Her ongoing work is a fulfillment of the vision she was given.

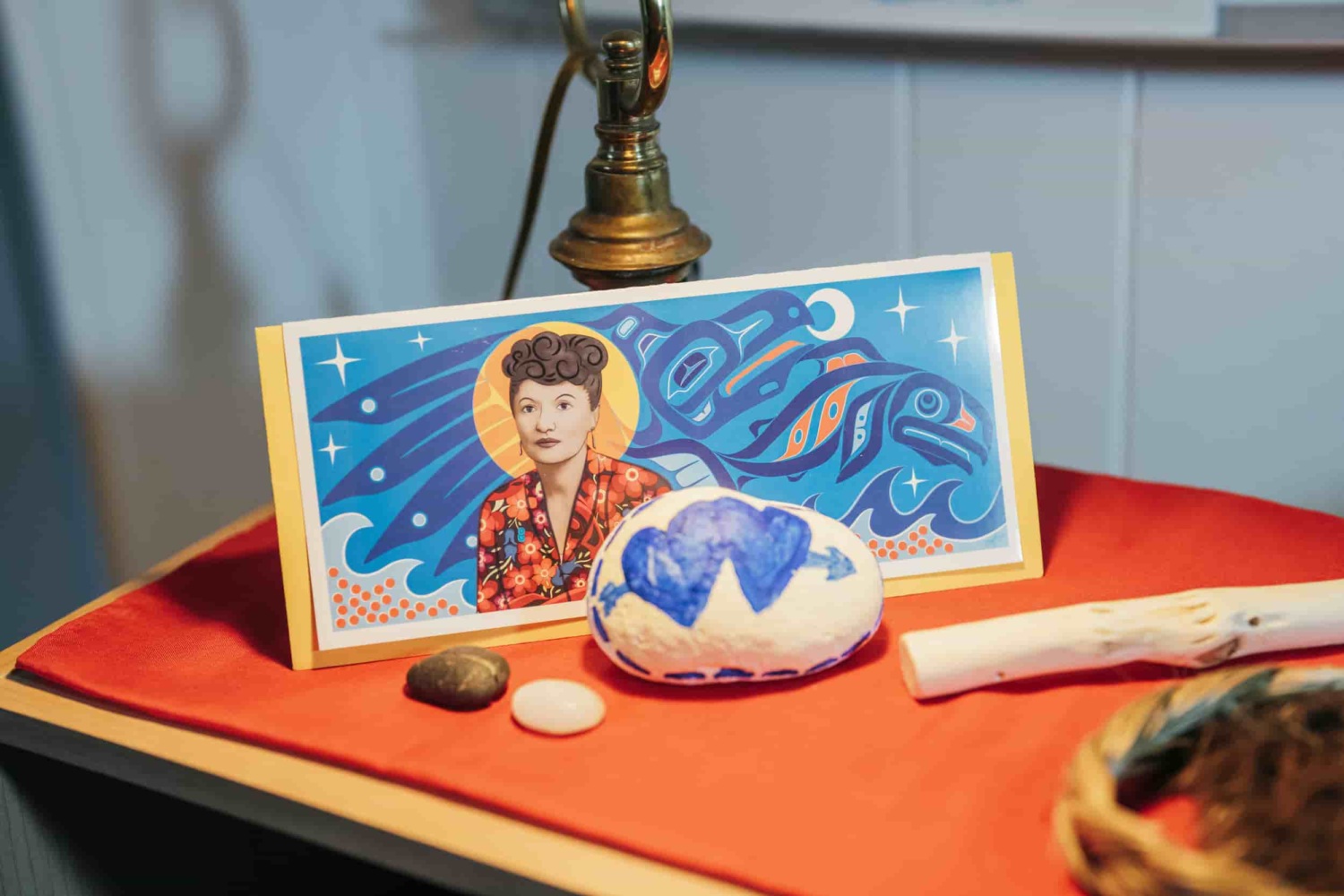

Jamiann is living the tradition started by Elizabeth Peratrovich (1911-1958), who was a Lingít civil rights leader and activist who fought for equal rights for Alaska Natives. She was a key figure in the passage of the Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945, the first anti-discrimination law in the United States.

Peratrovich is consistently seen as a civil rights leader on par with people like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Malcolm X, and she is credited for the passage of the first anti-discrimination bill in the Alaskan territory.

Jamiann is a strong advocate of talking and telling the truth about what has been done to Alaska Natives.

“Conversation opens a door into a subterranean world of raw unhealed wounds,” she said, then went on to point out how her grandmother told her of her memories of signs around her hometown that said, “No dogs or natives.”

She went on to tell of some of the atrocities carried out in the boarding schools, including those around Southeast Alaska.

“Starvation, sexual abuse, electrocutions, children being experimented on, locked in rooms for days on end, strap lines where kids were forced to whip other kids,” she somberly explained. “We have to talk about what happened if we are to heal from it.”

Language revitalization efforts, rebuilding local economies, and a growing Native food sovereignty movement are all projects Home Planet Fund’s partners are working on across Southeast Alaska. Jamiann’s healing work is an integral thread connecting all of this work.

While the last boarding school in the United States wasn’t closed until 1976, Jamiann is quick to point out that without healing, things like alcoholism, MMIP, drug addiction, domestic violence, mental health issues and other ripple effects from unhealed trauma become rampant.

The wide-ranging work of HTL and SSP is building healing bridges across the region now. Jamiann is working with the people of Kake, Alaska to help in their creation of a cultural healing center.

Through her advocacy she was instrumental in securing a public apology presented to the Village of Kake for a Quaker run mission school in the early 1900’s. The Alaska Quaker Friends Seeking Right Relations went on to donate $92,809 as reparations.

As we neared the end of our conversation, Jamiann quietly stood up with a stick of sage, and smudged each of us, and then the room; the energy of the space shifted from heavy and deep, to lighter and expansive within the time she wafted smoke around us.

Just days after we met, Jamiann traveled out to the village of Kake, to be there for an expected formal apology from the Navy for their bombardment in 1869.

She brought 155 S’áxt’ (devils club) protection sticks and gifted them to the community as representation to the number of years the community has awaited this monumental apology, and to signify a new path forward, a path towards healing.

This was but one of the dozens of healing opportunities on her whiteboard.