“We’ll certify ourselves as counselors of our culture. Because nobody knows our culture as well as we do.”Joel Jackson

Joel is no stranger to trauma.

His parents were sent to boarding schools. These so-called schools, like so many across the country that were set up by the US government and usually run by churches of various faiths, focused on converting Indigenous people to a lifestyle and belief system vastly different from their traditional culture. The children were kept apart from their families, and banned from practicing their cultures. This was aimed towards the dismantling of their connection to their communities and lands. Other kinds of abuse occurred in many of these schools, depending on the time period the schools were operational, their location, and the methods varied dramatically by generation.

The impact of these traumas continue to this day.

Joel told the story about how 30 years ago, there were 15 suicides in one year alone…in his village of less than 600 people.

“I have PTSD from dealing with the suicides of my friends while I was a policeman here,” he said from the front seat of the truck, as we made our way along a dirt road towards the building that is to become a healing center, driving through second and third growth forest on a rare sunny day in the Tongass rainforest of Southeast Alaska.

Tragically, Joel himself has lost several friends and family members to alcoholism.

His grandparents, who were of the first generation impacted by colonialism, became alcoholics as well. He sees unhealed intergenerational trauma as the root cause of the alcoholism and drug addiction plaguing the people of his village.

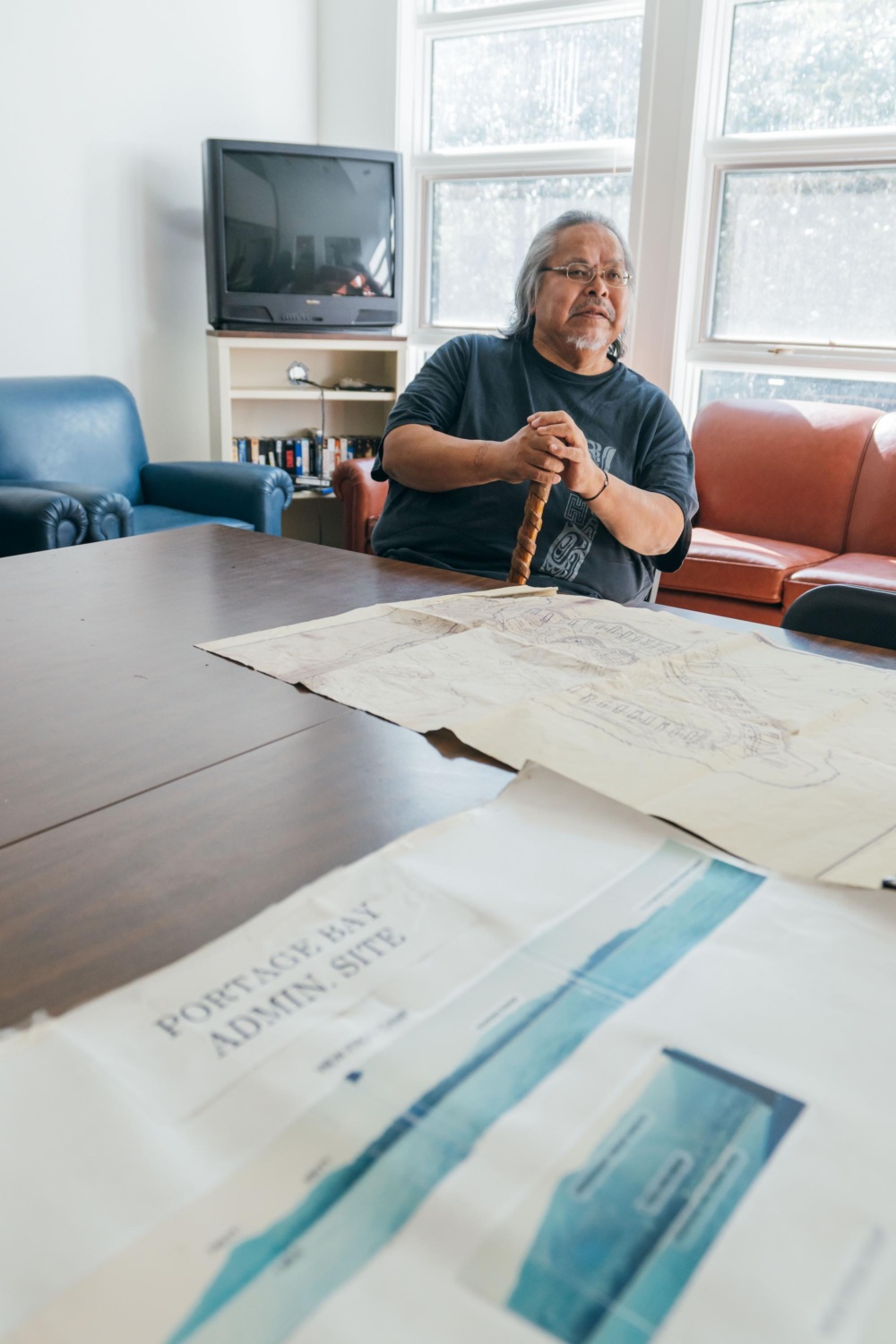

Now the president of the Organized Village of Kake, Alaska, Joel is on a mission to heal his people.

The building for the healing center will be rehabilitated and updated. There is no cell reception in its remote location, and the building has plenty of rooms, including a full industrial-sized kitchen, and sits amidst beautiful forest. Joel is quite pleased with the set up and condition of the building, given it is several decades old and in such a remote location.

When it is ready, the dozen people in it will be served by eight Native counselors who will bring in the cultural teachings. Joel hopes to hire primarily local Kake people to be counselors and train them up to do so. This will create local jobs for their community while strengthening the communities relationships to one another and their homelands.

“I want to teach them about plants, natural medicines, and hunting and fishing as part of their rehabilitation. The people we help may have forgotten these things, or never known them in the first place.”Joel Jackson

During the 1890s the Quakers built a mission in Kake. The federal government then handed the mission over to the Presbyterian Church, which went on to operate a school there which was guided by their faith, setting in motion the seeds of intergenerational trauma that continue to this day. Although no overt abuse was reported, a faith and culture that was not their own was imposed upon the children who attended.

“I never knew anything about intergenerational trauma until I attended an AFN [Alaska Federation of Natives] conference,” Joel had explained during our three hour drive out to the building. “That is when I realized how it is passed down through the generations and how deeply it impacts our people.”

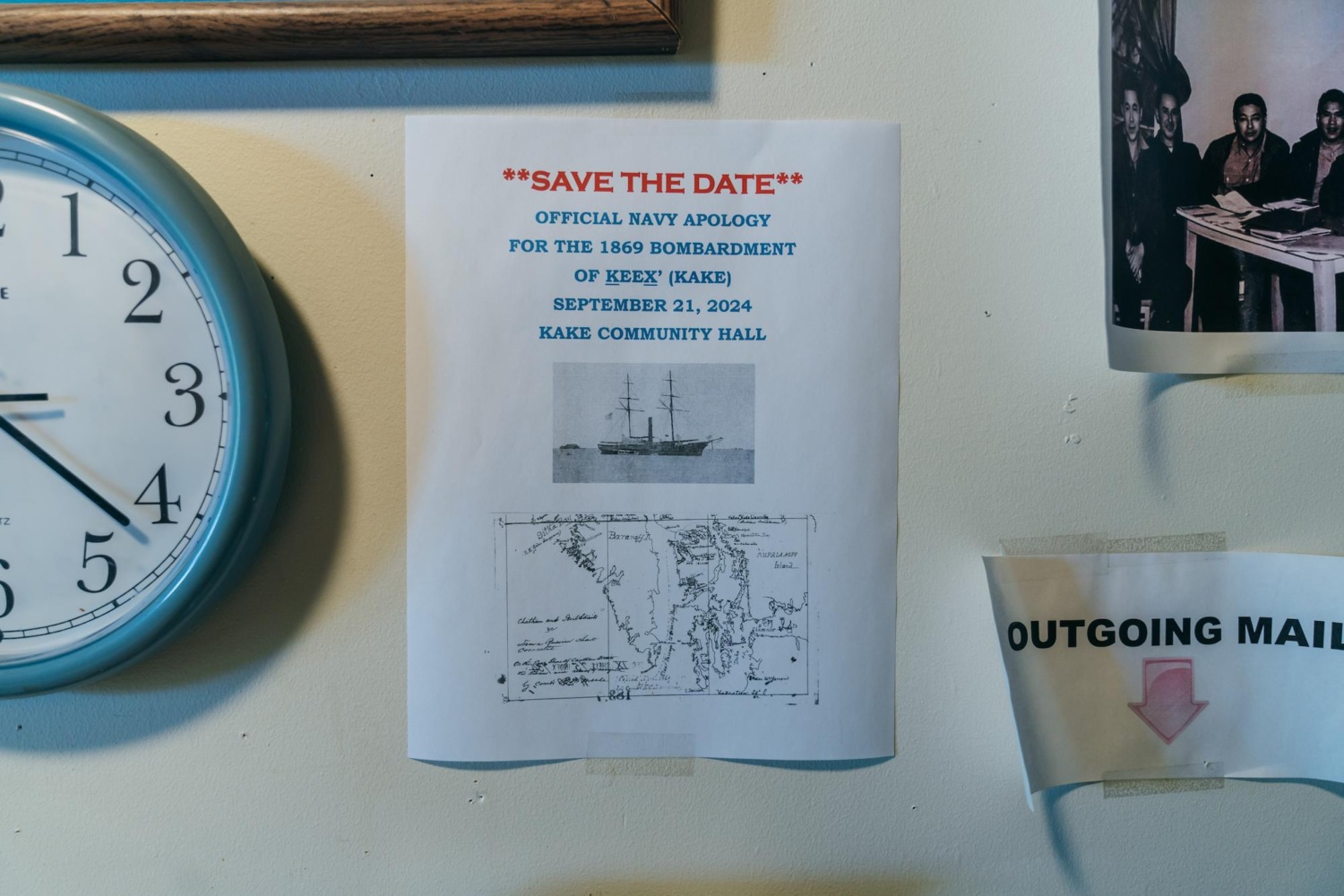

Another layer of trauma that preceded the school occured in 1869 when the US Navy bombed, burned, and looted the village during the winter. All of the inhabitants were displaced, and many died as a result.

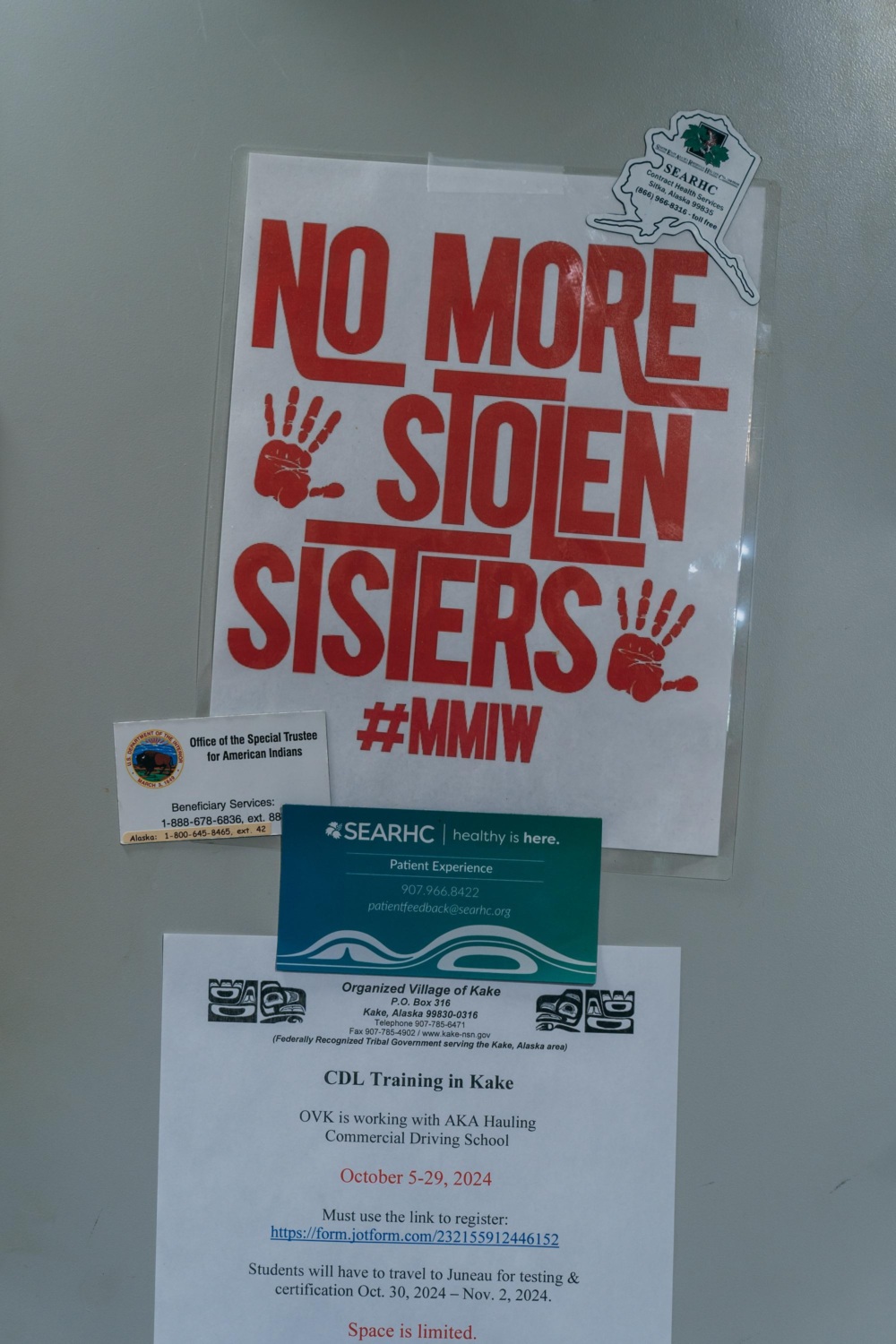

“We can’t do anything until we start healing from this,” Joel explained. He went on to explain that the healing begins with apologies and recognizing our histories. Joel has worked with partners across the region, including SSP Healing Catalyst Jamiann Hasselquist to right relationships and begin the community healing process.

His aims for the healing center are not just for his village, but for small communities around the entire region of Southeastern Alaska who are often underserved when it comes to getting the care they need.

The energy from Joel’s service work is already netting results, even in advance of an operational healing center.

A formal apology to the Alaska Native community for the harms caused during the mission was issued by the Quakers in Kake in 2024. This occurred on “Kake Day,” an annual celebration for when the village became recognized by the US as a city in 1912.

Residents of Kake also became the first Alaska Natives to be granted US citizenship and have the right to vote. However, this came at great cost. When this happened, the mayor had residents “put a lid” on their culture, because he believed harm came to the community from practicing their culture.

The Healing center represents a substantial shift from this.

The Quakers, who now call themselves the Friends Mission Church, have now gifted over $93,000 to support the healing center, along with their formal apology.

Their members have also been persistent in offering their help in the rehabilitation of the center, and any other work that needs to be done in order for it to begin serving people.

Another act of healing occurred during September 2024, when the US Navy sent representatives to Kake and formally apologized for its bombardment of the village.

Joel sees all of this as “a good start to the healing” and made it clear there are no hard feelings, especially since the relationships are now actively being healed.

He added, “They [Friends Mission Church members] are chomping at the bit to come help with the building, and we appreciate them for working with us and wanting to learn more about our culture.”

Dancing, carving, weaving, and ceremony will all be used as part of the healing and rehabilitation of the people who come to the healing center.

Joel also gleans hope from Shaelene Grace Moler, a Tlingit woman who drove us to view the building while sharing the day with Joel.

Having grown up in Kake, twenty-five-year-old Shaelene works for Spruce Root as the Sustainable Southeast Partnership (SSP) Communications Catalyst. SSP and Spruce Root, partners of Home Planet Fund, work to strengthen cultural, ecological and economic resilience across Southeast Alaska, an area covered by the Tongass Rainforest.

For Joel and others of his generation, young leaders like Shaelene represent the power and strength of what their culture can do.

The tribe’s ongoing youth culture camps have been part of an effort to rectify the ongoing problems of alcoholism, drug addiction and suicides in his village.

The annual camps serve to teach children and others their native language, dancing, carving, weaving, and other activities steeped in their culture, similar to what Joel intends for the healing center.

“I know that culture heals. These culture camps taught kids who they were, and to be proud of that, and that seemed to turn things around. Thankfully, that stopped the suicides.”Joel Jackson

As we walked back to the truck to begin the journey back to the village, Joel explained his intentions of getting residents of the healing center back onto the land and waters. He was raised in the old ways, but as he put it, “walked in two worlds,” living in a new culture that was imposed upon them, but all the while continuing to fish, harvest blacktail deer, grouse, and live very much within his traditional culture.

We climbed back into the truck and began the journey back to Kake.

Joel expects the healing center to be up and running within five years.

“The time is right to start healing our people,” he said, as we passed cedar and hemlock, and the occasional area of old growth forest. “Without healing, our people aren’t going to get anywhere.”

“For us, there is no better way to heal than by teaching our traditional ways. If we can do this, it will serve as a model for anyone else who wants to do this. I believe in it. Our culture will heal our people.”Joel Jackson